As we get older, we cannot help but look back more and more. It’s inevitable – life is mostly about memory, and it’s often not even for nostalgic reasons. We’re faced with endless revivals and reissues and reboots, and Facebook reminding you it’s exactly eight years since you wore that hat, but it’s also that, in the digital age, the present is full of the past. There has never been so much ‘past’ hanging around before, and even if you are determined to keep up with new albums, TV shows, books and films, elements of them will still ping inside your head: motifs, emblems, patterns, that unavoidably hark back to past experiences.

As we get older, we cannot help but look back more and more. It’s inevitable – life is mostly about memory, and it’s often not even for nostalgic reasons. We’re faced with endless revivals and reissues and reboots, and Facebook reminding you it’s exactly eight years since you wore that hat, but it’s also that, in the digital age, the present is full of the past. There has never been so much ‘past’ hanging around before, and even if you are determined to keep up with new albums, TV shows, books and films, elements of them will still ping inside your head: motifs, emblems, patterns, that unavoidably hark back to past experiences.

Two recent events I attended found their respective creators also wrestling with memory and how it floods their present day lives. David Baddiel’s My Family: Not the Sitcom, a jet-black but celebratory show about the eccentricities of his family background, has just completed its third theatrical run in London. I saw it two nights before it closed. Baddiel’s mother died just before Christmas 2014, when his father was already in the advanced stages of a dementia illness called Pick’s Disease, and the show finds Baddiel grappling with the dilemma of how to remember and portray those who are no longer ‘with us’, either literally or figuratively. It’s a complex show (but very funny), and it uses a variety of illustrative sources: photographs, documents, footage and correspondence.

I first encountered David Baddiel’s comedy on The Mary Whitehouse Experience in the early 1990s; his stand-up was a combination of pop culture and sport (much of it exhuming the forgotten flotsam of his 1970s boyhood) and a frank, often unflinching gaze into ‘difficult’ areas: death, sex, illness, and even occasional glimpses into his own family life when growing up in North London. I sometimes wondered how his parents might have reacted to this particularly confessional type of comedy, but as he outlines in the new show, they seemed fine with it – after all, they came to lots of recordings, especially his mum. But I also found myself thinking about how pop culture is not mere nostalgia in our formative years – it’s a kind of furniture around us, a way of connecting us to the wider outside world.

The night after I saw David’s show, I saw the pop trio Saint Etienne perform live at the Royal Festival Hall, the same day that they released a new album, Home Counties. As ever, they continue to blend the contemporary (glossy, tuneful, often danceable) with elements that yearningly evoke the past. In their case, they use folk elements, mood music, what used to be called ‘easy listening’, and a smattering of references to TV, film and trivia. The effect can be both delightful and haunting.

Like Baddiel, Saint Etienne also use evocative visual accompaniments in their live act: archive film, animation, montages and graphics. During one song, ‘I’ve Got Your Music’, complete with period footage of Sony Walkmans, I kept giggling – sometimes a little nervously – at the recurrent use of Cliff Richard on rollerskates from the ‘Wired for Sound’ video. You can’t get rid of memories, not even – in fact, least of all – trivial ones. Least of all trivial ones. They keep nudging and distracting you.

On Home Counties, there are some short interlude tracks which allude directly to broadcasting that celebrates the past: The Reunion (a Radio 4 discussion about a past event) and ‘Popmaster’ (Ken Bruce’s enduring phone-in quiz on Radio 2). But on some earlier records in the 1990s, they used lo-fi samples from television and film: Peeping Tom, Billy Liar, Brighton Rock, House of Games, a Chanel No. 5 TV advert from 1970, a record about understanding decimalisation, and a pioneering fly-on-the-wall documentary called The Family, about an ordinary suburban family in Reading.

The effect of these extracts was disorientating. It evoked the feeling of how, as young children, our encounters with popular culture – the world at one remove – are often accidental and out of our control. At some point, I suppose when school enters the picture, when we have to start remembering things, we progress beyond a few snapshots and start to find ourselves living a more or less linear experience. From there on, it’s not that we remember everything; it’s just that we start to piece things together, and try and make sense of our surroundings.

For me, this point would lie in the summer of 1974, the long break between nursery school and actual school. I had just turned four years old, an age when you’re still mastering the basics of early life and so you’re forever in the present. You have no idea what is going to register so strongly in your subconscious that you will never forget it. Quite often, it’s not the big events, but the trivia. Forty-three years later, I can isolate actual moments in my memory. And they’re nearly all related to television, or at least contexualised by television. Yet they’re not the big events. No memory of the World Cup in Germany, or a US president forced to step down in disgrace, or either of the two General Elections. I’d like to be able to claim that I recall Victoria Wood winning the talent show New Faces, or Abba winning the Eurovision Song Contest – but I don’t. And I didn’t see The Family either, at least not till the repeats in the late 1980s.

So I was fascinated by television – indeed, I cannot remember a time when I wasn’t watching television, just as I cannot remember a time when there wasn’t music in the house, or a time when I wasn’t reading books. And so, my early memories – even if they don’t feature TV or pop or books – are determined by those contexts. For some reason, I have an unusually vivid memory for date recall – not faultless, but I can usually work out to the day when something happened. And because the Internet now exists and there are sites like the remarkable BBC Genome project, which has every BBC TV and radio schedule between 1923 and 2009, it is actually possible to cross-check these kinds of early memories to the exact day. (If I were a child now, in the on-demand world, this would be practically impossible to monitor.)

It was relatively easy to be obsessed by television in the first half of the 1970s as there wasn’t that much of it. There was no CBeebies or Nickelodeon. There were three channels, there was at most about 12 hours of children’s television a week, mostly in the late afternoon, and there were lots of intermissions and interludes, a lot of waiting. You even had to wait a few minutes for the television to warm up when you switched it on.

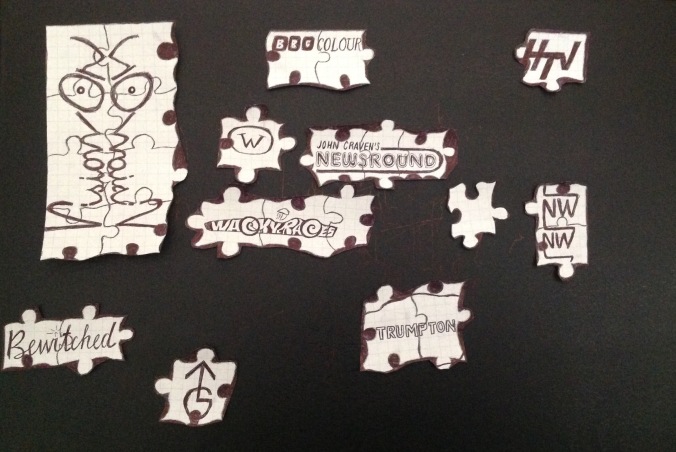

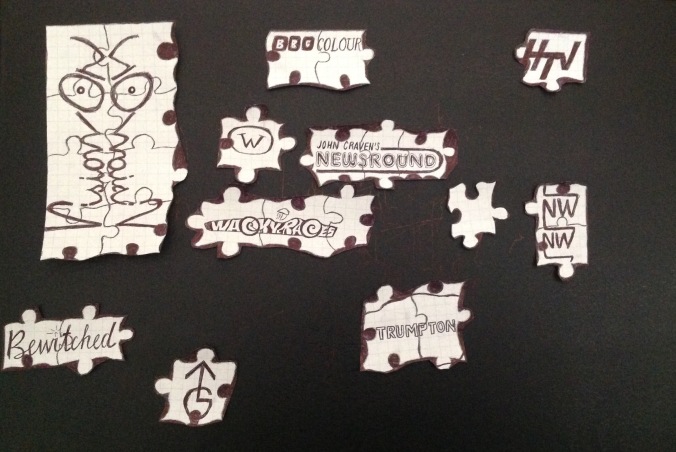

I felt like I wanted to own television, the way I owned books. And, in the days before video, not everything had a spin-off book or LP record. So how did I do that? Well, the answer is obvious: I tried to reproduce logos, graphics from TV shows and station idents. (I did play with Lego as well, honest.)

My favourite programmes were mostly visually driven: cartoons, Sesame Street on Saturday mornings, and a lunchtime show on ITV called Pipkins, which was like a comic serial for the under-fives featuring actors and puppets, and which on 5 August that year dealt with the death of the programme’s lead actor George Woodbridge by confronting the death of his character head-on. Quite groundbreaking. Did I watch that one? Frustratingly, I’m not sure – that memory is not there.

But my very favourite programme was called Vision On, ostensibly for hearing-impaired children but which appealed to them – and consequently a wider audience – by disregarding verbal content and concentrating on visuals: short films, animation, mime, surreal and comic sketches, and art demonstrations by the brilliant Tony Hart. Any speech that did remain was accompanied by sign language from his co-host Pat Keysell.

At the heart of Vision On was, I guess, was an early exercise in interactivity. ‘The Gallery’ was an invitation for young viewers to send in original artwork to the BBC and be rewarded with five vital seconds or so onscreen. The accompanying music is now an obligatory soundtrack to anything to do with painting: to those of us of a certain age and above: ping, Vision On.

I wasn’t particularly good at drawing, but I was already somehow skilled at lettering – and I was fascinated by the Vision On logo. Tony Hart, who created it, named it ‘Grog’, a symmetrical cross between a grasshopper and a frog. I could have just painted Vision On on some paper or card, and then folded it over to get a mirror image, but that would have been much too straightforward. Instead, I actually tried to copy the Grog from memory, without the image in front of me. I now realise that trying to copy something exactly can be harder than creating something. I was so committed to getting it right that I momentarily considered sending my best result off to the programme, before reasoning that they probably wouldn’t have needed it. Vision On already have their own Grog, Justin. It’s a big one, on their wall, behind them, every week.

Sometimes I found television funny; sometimes it made me feel funny (Samantha off Bewitched, that woman off Hickory House, and a classical violinist I kept seeing on BBC2 – probably the young South Korean virtuoso, Kyung Wha-Chung). At other times, in the blink of an eye, it could turn into something utterly anxiety-inducing. There were public information films straight after children’s programming which alerted you to a world of road accidents, rabies, drowning in lakes full of shopping trollies, glass on the beach. There were other alarming things in the world: people also seemed to find The Osmonds dangerous and kept screaming at them on TV. (You remember that public information film: BEWARE OF OSMONDS.) I didn’t like the look of the ATV logo at all, and it was hard to draw. The dubbed monkey shrieks on Daktari – horrid.

Furthermore, there was some frightening regional thing after Sesame Street on Saturdays called Orbit, in which a doubtless well-intentioned announcer called Alan Taylor pretended to be in space (rather than a weather forecast studio in Bristol) with only a buzzing gonk called Chester for company. Alan Taylor, for reasons I have never quite processed, absolutely put the fear of God into me. The three minutes of Orbit that survive here – and I defy you not to sing along with the opening theme – provides no clue about what they might have filled the rest of the half hour with. Cartoons from Spain? Showjumping highlights? It’s going to be birthday greetings, isn’t it?

This was all disorientating and scary and yet I couldn’t back out. I had joined a story I didn’t yet begin to understand, but was determined to make sense of. Is that Bernard Cribbins singing the Wombles theme? Why do we keep being told ‘watch out watch out watch out watch out there’s a Humphrey about’? Why is television closing down now with some music – is it tired? Why is Alan Taylor doing this programme as well? Does he ever go home, and please can he do that? And oh god, why ‘The Laughing Policeman’, at all, ever?

And then, somewhere in the background which perhaps should be in the foreground of these memories, there was real life. And I strangely don’t remember much of that. I’m sure I went to the beach a lot with my family, and shopping, and played games with my brother and so on. My twin cousins were born that summer – they lived nearby but I don’t remember the event itself. Maybe I was too busy watching Wait Till Your Father Gets Home to notice.

But all my early hazy memories have television in there somewhere. The first definite early memory I have is of my nursery school teacher, who owned two Labradors, telling us it was time to watch Play School. So that can’t be later than about June or July 1974. I can remember being on the back seat of a relative’s car snoozing while they went into a shop, and for some reason I can remember it was a Wednesday, and for some even stranger reason I remember that I’d just watched an episode of the stop-frame animation series Barnaby. (Summer 1974, but no later.)

In late August 1974, one week before I started school, we visited Birmingham, partly to stay with friends of my parents, but also probably because my paternal grandfather lived nearby, in Sutton Coldfield. I remember arriving in Birmingham on the Sunday afternoon: 25 August 1974. You must remember!: The Golden Shot was about to start. Three days later, on Wednesday 28 August, after Teddy Edward and Derek Griffiths’s Ring-A-Ding and that’s how I can be sure, we visited my grandfather. Or at least we visited his house. I do not remember my grandfather – I just remember a rather messy house. I sat in some kind of living room area – the decor was brown as most things in the seventies were. My brother may have also been there. My mum definitely wasn’t. I don’t remember much else – perhaps it was because the television wasn’t switched on.

This is all a bit embarrassing. Maybe I had tunnel vision, and didn’t like people very much. Or maybe it’s just that it’s harder to put a timeframe around real life. Unless you were diligent enough to put a date on the back of a photograph back then, you’d have to guess, and that’s not always easy. But in fairness, television is a powerful medium: colourful, urgent even in those more languid days, and yes addictive. But it taught me a lot, and one thing it did was start to explain things to me. Like music, it has frozen memories in time, a counterpoint to everything else that was going on.

I started school on Monday 2 September 1974, but I still went home at lunchtime to watch Pipkins. My grandfather died on Saturday 19 October 1974. But I have no memory of that.

Saint Etienne’s Home Counties is out on Heavenly Records.

David Baddiel’s My Family: Not the Sitcom has completed its London run, but tours the UK in 2018 and 2019.

Andrew O’Hagan’s new book, The Secret Life, consists of three essays. The first of them, ‘Ghosting’, is itself about the process of writing, and his experience of trying to ghostwrite Julian Assange’s autobiography for Canongate Books, only to find that Assange cannot or will not commit to writing or exposing his real thoughts and feelings, who long ago gave up any professional and objective integrity for self-absorption and a studied cult of personality. Leaving aside everything else about Assange (and there is a lot of everything else about Assange), I keep picturing him as a man who spends a lot of his time staring in the mirror, stroking his hair while fantasising about being interviewed. ‘That was the big secret with him,’ writes O’Hagan at one point, ‘He wanted to cover up everything about himself except his fame.’

Andrew O’Hagan’s new book, The Secret Life, consists of three essays. The first of them, ‘Ghosting’, is itself about the process of writing, and his experience of trying to ghostwrite Julian Assange’s autobiography for Canongate Books, only to find that Assange cannot or will not commit to writing or exposing his real thoughts and feelings, who long ago gave up any professional and objective integrity for self-absorption and a studied cult of personality. Leaving aside everything else about Assange (and there is a lot of everything else about Assange), I keep picturing him as a man who spends a lot of his time staring in the mirror, stroking his hair while fantasising about being interviewed. ‘That was the big secret with him,’ writes O’Hagan at one point, ‘He wanted to cover up everything about himself except his fame.’ As we get older, we cannot help but look back more and more. It’s inevitable – life is mostly about memory, and it’s often not even for nostalgic reasons. We’re faced with endless revivals and reissues and reboots, and Facebook reminding you it’s exactly eight years since you wore that hat, but it’s also that, in the digital age, the present is full of the past. There has never been so much ‘past’ hanging around before, and even if you are determined to keep up with new albums, TV shows, books and films, elements of them will still ping inside your head: motifs, emblems, patterns, that unavoidably hark back to past experiences.

As we get older, we cannot help but look back more and more. It’s inevitable – life is mostly about memory, and it’s often not even for nostalgic reasons. We’re faced with endless revivals and reissues and reboots, and Facebook reminding you it’s exactly eight years since you wore that hat, but it’s also that, in the digital age, the present is full of the past. There has never been so much ‘past’ hanging around before, and even if you are determined to keep up with new albums, TV shows, books and films, elements of them will still ping inside your head: motifs, emblems, patterns, that unavoidably hark back to past experiences.